Saving babies at the edge of life

From ground-breaking research to minimise brain damage to bespoke psychological support for parents, Evelina London’s neonatal specialists explain what makes one of the largest neonatal units in the country, one of the most outstanding.

(Disclaimer: these articles discuss themes that may be upsetting to some readers.)

A difficult start

A difficult start

Most of the babies admitted to the neonatal unit, with its gleaming floors and sealed rooms, are there because they were born prematurely, often extremely so. As miniature human beings, they lack the subcutaneous fat that develops in the last month of pregnancy, which gives full-term babies the fat, glossy look of the newborn.

Survival rates have improved enormously, even for those delivered before 28 weeks. But there is much progress still to be made. The risks for those born extremely premature include cerebral palsy, learning difficulties and an increased risk of mental health problems.

Some have had surgery or endured infections. Others have gut or growth problems. Among the incubators with their flashing lights and beeping alarms, the future of scores of families hangs in the balance. This is medical technology at its most sophisticated. Yet as every parent of such a baby knows, progress is never smooth.

The hope and expectations among parents have risen, says lead nurse, Alex Phillips. “Often when parents hear there is only a very slight chance of survival they will still seize it,” she said. Even where the prognosis is very poor, parents understandably fight for their baby. It’s important not to offer personal opinions but to provide simple, non-judgmental support. “We need to accompany them on their journey.” That journey is always fraught - and can be long. Some babies remain more than a year on the unit, cared for by its 50 doctors and 190 nurses. It is one of the largest neonatal units in the country.

That journey is always fraught - and can be long. Some babies remain more than a year on the unit, cared for by its 50 doctors and 190 nurses. It is one of the largest neonatal units in the country.

But what makes Evelina London unique is its proximity to the large maternity unit at St Thomas’, Evelina London’s own comprehensive paediatric services at the end of the corridor and St Thomas’ adult services across the courtyard. For some, it is a one-stop shop for life.

Geraint Lee, consultant neonatologist and head of service for the unit, said: “To know that the kidney doctor you met when your child was born is the same as the one treating him now he is 16, or that the neurologist managing your child’s seizures is the same now she is a teenager – that is quite something. Continuity matters. The patient and family are at the centre of what we do – that is genuinely the case here.”

Cooling for healing

Cooling for healing

For at least the last 40 years paediatric orthodoxy has dictated that babies should be kept warm. Hypothermia is a real threat in the newborn, who lack the capacity to respond to cold by shivering.

But specialists now working at Evelina London turned that view on its head with the discovery that cooling babies who had suffered birth trauma could save them from brain damage.

In the neonatal unit, doctors and nurses working at the limits of medicine face desperate challenges. Birth asphyxia (a medical condition resulting from deprivation of oxygen) is one of the greatest. Sometimes caused by the umbilical cord becoming wrapped around the neck, it affects one in 1,000 babies in the UK and can have a devastating impact. Hundreds are left with permanent disabilities each year.

The consequences of birth asphyxia are far-reaching. The lifelong costs of care for a severely brain-damaged baby can be as much as £5 million. Often, there is no warning of a problem until the very last days of pregnancy, or during labour.

David Edwards, professor of children’s and neonatal medicine at Evelina London, has spent over 20 years trying to mitigate the damaging effects of oxygen deprivation at birth. He and his team found that what worked best was reducing the temperature of the brain.

Although it is well known that cooling can aid survival - from extraordinary stories of explorers falling through the ice and surviving after as much as half an hour underwater – this was different. It involved cooling after the brain had been starved of oxygen. It had been thought that any restriction of blood flow to the brain caused damage within minutes.It turns out that the brain doesn’t die immediately after the oxygen supply is cut off – and MRI scans proved it. It also emerged that the brain is exquisitely temperature sensitive – only a few degrees of cooling can slow the cascade of reactions that leads to permanent damage. But there is a narrow window – if cooling does not begin swiftly following the trauma, the opportunity is lost.

Although it is well known that cooling can aid survival - from extraordinary stories of explorers falling through the ice and surviving after as much as half an hour underwater – this was different. It involved cooling after the brain had been starved of oxygen. It had been thought that any restriction of blood flow to the brain caused damage within minutes.It turns out that the brain doesn’t die immediately after the oxygen supply is cut off – and MRI scans proved it. It also emerged that the brain is exquisitely temperature sensitive – only a few degrees of cooling can slow the cascade of reactions that leads to permanent damage. But there is a narrow window – if cooling does not begin swiftly following the trauma, the opportunity is lost.

Sophie Miles, 5, is testament to the success of what is called “hypothermic rescue”. Her mother Emma was 35 weeks pregnant when she noticed her unborn baby had stopped moving. She had an emergency Caesarean the same day but doctors feared Sophie had already suffered severe brain damage. She was transferred to Evelina London and placed in a water cooled jacket for three days reducing her temperature from 37 degrees to 34 degrees.

Today, Sophie is a healthy, lively schoolgirl. Her father Ben said: “Sophie has shown no signs of developmental delay and is now a happy, bubbly child who loves dressing up as Disney princesses. You would never know she had such a difficult start.”

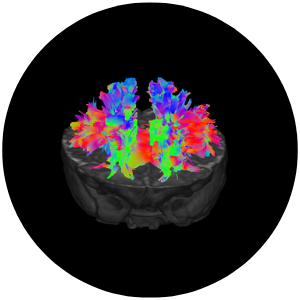

The practice of using cooling to prevent the damaging effects of birth asphyxia has now spread worldwide. For Professor Edwards, however, this is only the beginning. “Cooling is not a panacea,” he says. It helps only about a third of babies affected, and his team is now working on developing drugs to improve the outcomes still further, using brain imaging to assess their impact. New approaches to imaging, pioneered at Evelina London, have enabled the moving fetus to be scanned, and even blood flow through the heart to be pictured.

“It took us 10 years to prove cooling worked. With the ground-breaking advances in scanning we are seeing, we will be able to test the effect of drugs much more quickly.” he said.

Delicate human beings demand ingenuity

Delicate human beings demand ingenuity

Birth trauma is only one of the challenges faced by the neonatal specialists.

Looking after such delicate human beings demands ingenuity. Babies need human contact – research shows that positive touch can help them settle, bringing down their heart rate and oxygen consumption. But although parental involvement is always encouraged, they cannot be present all the time. Nurses will then lay across their tiny charges a Zacky Hand – a hand-shaped cushion - to provide the reassuring sense of containment that they would otherwise have in their mother’s arms.

Along with colleagues in the maternity department, they have devised a “red hat” alert system to identify babies at risk of hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar). Those in need of close monitoring wear a woolly red hat to remind nurses and midwives to make regular checks.

A psychologist provides support to parents who cling to hope as their babies cling to life. Having a baby in the neonatal unit is one of the commonest causes of mental trauma in paediatric care. Further work is underway to improve the environment and facilities for parents. The work is part of an internationally recognised movement to maximise family-integrated care so that parents are supported to be involved in their baby’s care from as early as possible. It’s crucial for the health and wellbeing of both the child and parents that they care for their baby from the very start, supporting early brain development of the child and the vital early bond between a baby and their parents, despite the challenging circumstances. The unit redevelopment plan follows extensive consultation and co-design with parents.

At the cutting edge of research

But the unit is also at the cutting edge of research, a position cemented by the launch of the Institute of Women and Children’s Health, overseen by King’s Health Partners and hosted by Evelina London.

By combining medical care and research for women and children, the new institute will improve understanding of serious diseases and, uniquely, embrace both physical and mental health.

One of the key research studies underway is into the origins of autism. There is an increasing belief among psychiatrists that the condition may arise in babies born with a genetic vulnerability who are then subject to environmental pressures – and one of those pressures may be prematurity.

One of the key research studies underway is into the origins of autism. There is an increasing belief among psychiatrists that the condition may arise in babies born with a genetic vulnerability who are then subject to environmental pressures – and one of those pressures may be prematurity.

For the study, Evelina London’s state-of-the-art imaging centre has scanned over 2,000 babies so far, before and after birth and at 6 months, to look at how the brain grows. “We have already found differences in the brains of children who went on to develop autism,” said Professor Edwards.

He adds: “Doctors will always ask about your family history – whether there is heart disease or cancer – but never ask about prematurity. Yet that has a far bigger influence. It has a massive influence on people’s lives. If we could stop prematurity, we could stop an awful lot of death and disease.”

Until that day comes, Evelina London’s neonatal unit will continue to manage the huge demand from hospitals across the country seeking specialist help.

Until that day comes, Evelina London’s neonatal unit will continue to manage the huge demand from hospitals across the country seeking specialist help.

“Consultants here are always wrestling with throughput of patients – how can we accommodate another family needing our care,” said Dr Lee. “Still, to any request, we try to say: “The answer’s yes, what’s the question?”

Pictured: Professor David Edwards; lead nurse, Alex Phillips; and Dr Geraint Lee

Pictured: Professor David Edwards; lead nurse, Alex Phillips; and Dr Geraint Lee

The ‘Spotlight on’ features were prepared for Evelina London by, Jeremy Laurance, health writer.

This article has been adapted for use online.